One thing you have to understand about Silicon Valley: We really don’t know what we are doing.

That’s not an indictment. We have wonderfully gifted people working at the edge of what is known, where great discoveries are made. But we can’t see the future of technology. And, as with most human phenomena, it turns out to be really hard to understand technology’s present, too.

That’s important for policymakers to keep in mind as they reckon with Silicon Valley. We don’t have some public policy for machine learning or computer vision or speech recognition, optimized for the Common Good, secreted away in the cloud. This stuff is genuinely hard. There is no policy playbook for emerging technologies.

Hence, it’s no dig on policymakers to say that, on technology, they are going to get it wrong. They are going to get it wrong because even those most knowledgeable about technology don’t understand its social impacts in the present, much less in the future.

That is not an argument for inaction. Rather, it is an argument for policy institutions that are both strong and humble: strong, in that they can act when then need to; humble, in that they recognize that even if they pinpoint the perfect policy regime for today, it will be wrong tomorrow. And often wrong for a generation, at least in our current system: A standard regulatory or legislative process can entail years of fact-finding and policy regimes that last decades.

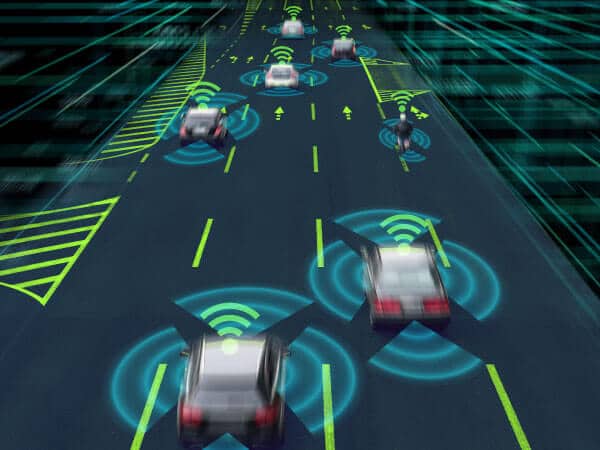

But new models are emerging. In 2014, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) acknowledged the coming emergence of automated vehicles, at a speed, scale and complexity that both required robust public sector engagement and made a folly of long-term rule-making. Rather than breaking out its standard regulatory tools, in September 2016 NHTSA rolled out 15 “guidelines” – which were not really guidelines at all, but areas in which the government saw a compelling public interest. Recognizing the speed with which the AV space was changing, they promised to refresh those guidelines within 12 months, leaving open the possibility that regulatory teeth could be applied for any of the 15 when circumstances demanded. Sure enough, one year later a second version was released, complete with “2.0” suffix. And, while the promised 3.0 version has not yet appeared now 16 months on, the cadence still suggests a rule-making sea change.

To an anxious public, NHTSA had a clear message: The government is on the case. It would be deeply involved in assuring an orderly transition to automated vehicles, with public safety at the core. To industry, it was an invitation for dialogue, a request for expertise, and an imperative: If we don’t handle these issues together, it’s going to be a problem for you.

One can argue whether NHTSA has moved too slowly or too quickly, or otherwise bumbled along the way. But the basic blueprint is promising when it comes to rapidly evolving technologies: a humble policy institution, designed to learn about new technologies and their impacts on society, and to iterate with them.

– Brian Brennan, Senior Vice President, Investor Relations and State and Federal Coalitions, Silicon Valley Leadership Group | July 25, 2019